|

|

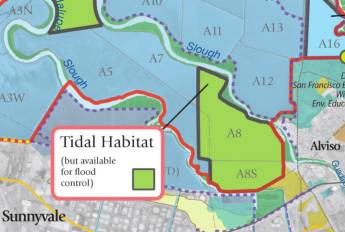

Scientists Find Increased Mercury in Birds & Fish Near Alviso One of the key challenges for the Project is how to manage habitats in parts of the South Bay where mud is contaminated with mercury from the largest historic quicksilver mine in North America. The old New Almaden mine site in the hills above San Jose is drained by the Guadalupe River into Alviso Slough and our surrounding Alviso Pond Complex. Our goal is to convert these ponds to wetlands in a way that won't result in fish and birds taking in more mercury, which can affect their health and reproduction. At the 1440-acre Pond A8/A7/A5 complex at the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge near Alviso, we built a 40-foot adjustable notch between Pond A8 and Alviso Slough, so we could experiment with making a small opening and then study the results.

Unfortunately, scientists' latest data on mercury in birds and fish at these ponds is concerning, showing large mercury increases resulting from construction activities in the pond and associated with the opening of the Pond A8 notch in 2011 to connect the pond with open waters.

Unfortunately, scientists' latest data on mercury in birds and fish at these ponds is concerning, showing large mercury increases resulting from construction activities in the pond and associated with the opening of the Pond A8 notch in 2011 to connect the pond with open waters.

Results include:

Researchers say these are very dramatic mercury increases in a short time period.

Researchers say these are very dramatic mercury increases in a short time period.However, there is a possibility that the mercury increases we saw in 2011 were short-term increases due to construction activities. We are continuing to study mercury in birds and fish this year. Project puts further notch widening on hold Researchers are also looking at how opening the Pond A8 notch will scour sediments in Alviso Slough, and potentially remobilize the buried mercury there. In June 2012, with preliminary results showing little remobilization of mercury in Alviso Slough sediments after we first opened Pond A8 five feet in 2011, US Fish and Wildlife Service managers decided to widen the opening from five to 15 feet. Given the new information on mercury in fish and bird eggs, managers have decided they will not open the notch any wider until further data indicates it would be safe to do so. How to improve the situation? Jim Hobbs, the UC Davis scientist studying fish at the Project, recommends that Pond A8 be opened year-round, or at least earlier in the spring -- it is now opened from June through mid-December. He concludes that keeping it open longer could improve pond water quality, as the pond is flushed with slough waters. Opening the notch earlier or year round would bring slough waters into Pond A8, and allow fish free movement. It could increase the abundance of prey fish species and create a productive estuarine nursery habitat for threatened juvenile steelhead. Mercury researchers from USGS also think that keeping the notch open year-round would be better, as opening and closing it each year may be continually perturbing the system. This could create conditions that increase methylmercury -- the form most toxic. They see the second-best option as opening the notch earlier so that nests are not flooded, and hypothesize that having water flowing through the pond might minimize methylmercury formation. Regulators, however, have been concerned that opening the pond during threatened steelhead smolt season could trap smolt in the pond and leave them vulnerable to predators. Project managers and scientists will continue to work with regulators to identify our best route forward for wildlife. Using a gated opening at Pond A8 has allowed the project to conduct one of its key adaptive management studies. Because of the scientific uncertainty about how the most dangerous type of mercury develops and makes its way into the food web, the Project's adaptive management studies create the opportunity to learn from our restoration actions. We can create scientific knowledge to help guide our future actions and inform other Bay Area land managers about the best ways to cope with mercury problems. For additional information, see this summary on the Project Science page. |

|

|

Unsubscribe from the newsletter. |

|