What Are Wetlands?

As the name implies, wetlands are lands saturated by or covered with salt and/or fresh water for all or part of the year which produces a unique ecosystem characterized by specific types of hydrology, soils, wildlife, and vegetation. Some of the more familiar names for different kinds of wetlands are swamps, marshes, mudflats, lagoons, and estuaries. Along the coast, they are frequently the transition zone between dry land (upland) and bodies of water. Wetlands can also be habitat inundated by surface or groundwater such as freshwater marsh, ponds or pannes. The water saturated soils of wetlands determines the type of plant and animal communities that can live in these specialized environments.

The wetlands that would be restored by the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration project are coastal wetlands. Coastal wetlands are typically salt or brackish depending on the quantity of freshwater inflow from a stream or rainfall. Some of these wetlands are seasonal wetlands because they are only inundated for part of the year. Plants that are specially adapted to the variation in the salinity and water level (due to tidal action and/or seasonal rains) will be found in coastal wetlands. These plants include pickleweed, cordgrass, gum-plant and salt grass.

Coastal wetlands are home to a variety of animals that either live year round or during some part of their life in the wetland. Numerous fish species, including topsmelt, arrow goby, staghorn sculpin, and starry flounder are residents of wetlands for all or part of the year feeding on the abundant invertebrate species that inhabit the wetland. Several of these fish depend upon the wetland for reproduction and rearing of juvenile fish. Regarding birds, endangered Ridgway's rails build platform nests in the marsh, whereas the threatened Western snowy plover nest and forage on tidal flats, sandy beaches, and salt ponds south of the San Mateo Bridge. Heron, snowy egret, salt marsh song sparrow nest near pickleweed and other marsh plants. Coastal salt marsh mammals include shrews, the endangered salt marsh harvest mouse, and other rodents live in the marshes. Harbor seals haul out (rest out of the water) in tidal areas in south San Francisco Bay. Coastal salt marshes are also home to insects such as the salt marsh water boatman, wandering skipper, and numerous species of beetles and flies, which graze on leaves and seeds, help pollinate the wetland flowers, and prey upon a variety of small animals.

References Used:

Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals, SF Bay Area Wetlands Ecosystem Goals Project

Feasibility Analysis: South Bay Salt Pond Restoration, Siegel and Bachand

Turning Salt into Environmental Gold, Save the Bay

Wetland Restoration, EPA fact sheet 843-F-01-002e

Wetland Overview, EPA fact sheet 843-F-01-002a

The Ecology of San Francisco Bay Tidal Marshes: A Community Profile, FWS/OBS-83/23

Why Do We Need Wetlands?

Wetlands are important for many reasons. They provide important habitat for diverse communities of plants and animals, including over 50 percent of the federally listed threatened or endangered species. Wetlands provide wintering habitat for migratory waterfowl; in the Bay Area, the wetlands along the Estuary are very important feeding and resting areas for birds migrating along the Pacific Flyway. Wetlands also direct spawning and rearing habitats and food supply that supports both freshwater and marine fisheries.

Nearly 80 percent of the Bay's original wetland habitats have been diked and filled for farming, grazing, salt extraction, building and other development. This loss of wetlands has greatly reduced the amount of habitat available to many species of fish and wildlife. Several local animal and plant species, including the salt marsh harvest mouse and the Ridgway's rail, have been listed as endangered as a direct result of the reduction in extent and quality of their wetland habitats. Many other species, including migratory shorebirds, waterfowl, and numerous fish species, also have been affected by this loss of habitats.

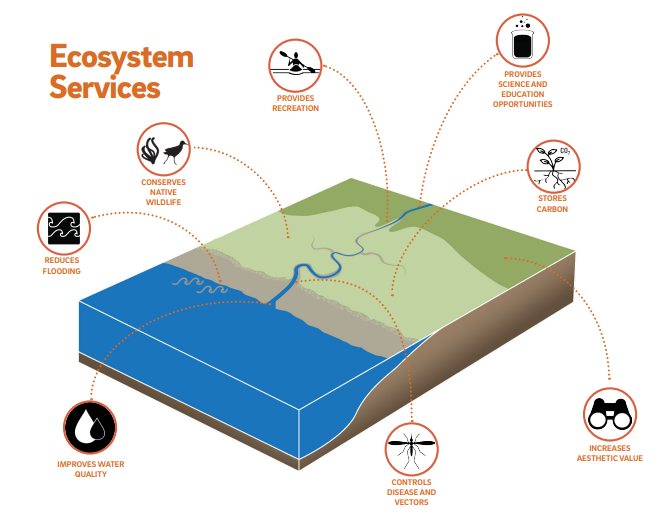

Wetland habitats play key roles in maintaining both a healthy ecosystem and economically vibrant region. Besides providing fish and wildlife habitat, wetlands also improve water quality, protect lands from flooding, provide energy to the estuarine food web, help stabilize shorelines against erosion, and increase groundwater availability. Wetlands also support extensive outdoor recreation. Wetlands offer a broad range of non-biological benefits that include:

WATER QUALITY

Wetlands can serve as natural remediation sites by enhancing water quality. Many human and household wastes, toxic compounds, and chemicals such as fertilizers are tied to sediments that can be trapped in wetlands. Plants and biological process in wetlands break down the convert these pollutants into less harmful substances.

RECREATION

Wetlands also contribute to the community through recreational activities such as fishing, hunting, and bird watching. It is estimated that the annual economic value of wetlands statewide in California is between $6.3 and $22.9 billion. The 1996 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation reported that 3.1 million adult Americans hunt migratory birds including geese, ducks, doves, and other game birds. Nationwide, it is estimated that hunters spend about $1.3 billion on travel, equipment, and other associated expenses.

FLOOD MANAGEMENT

Wetlands can not only serve as biofilters, but they can also slow down and soak up water that runs off the land. Wetlands are capable of lowering the volume of floodwaters and diminish flood heights which in turn reduce shoreline and stream bank erosion. Preserving natural wetlands can reduce or eliminate the need for expensive flood control stuctures.

ECONOMIC VALUES

The vast majority of our nationís fishing and shellfishing industries harvest wetland-dependent species. This catch is valued at $15 billion a year. The economic benefits of wetlands also extend to other forms of commercial harvesting such as shell mining in the South Bay. The South Bay formerly had one of the nation's most productive oyster beds with its harvest serving much of the West Coast.

References Used:

Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals, SF Bay Area Wetlands Ecosystem Goals Project

Feasibility Analysis: South Bay Salt Pond Restoration, Siegel and Bachand

Turning Salt into Environmental Gold, Save the Bay

Wetland Restoration, EPA fact sheet 843-F-01-002e

Wetland Overview, EPA fact sheet 843-F-01-002a

Types of Wetlands, EPA fact sheet 843-F-01-002b

Restoring the Estuary: An Implementation Strategy for the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture. January 2001

What Kinds of Wetlands Are Included in the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project?

The South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project would help create, enhance, and preserve a variety of wetland types. The predominant wetland types that occur or may occur in the project area include shallow subtidal areas, tidal mudflats, tidal marsh, salt ponds, muted tidal/managed ponds, and seasonal wetlands. Small areas of riparian corridors and freshwater marshes are present in the creeks flowing into the South Bay. Although not technically a wetland, upland transition zones will be an important component of marsh preservation and restoration. The various wetlands types are briefly discussed below.

TIDAL MUDFLATS

Tidal mudflats are intertidal areas covered twice a day by the Bay's high tides. These expanses of mud support an extensive community of shellfish, snails and other invertebrates, as well as algae and eelgrass. During high tide, fish feed in the shallow waters covering the mudflats, and during low tide when the mudflats are exposed shorebirds come to feed. Tidal flats are extremely important for wintering waterfowl and shorebirds. Given the South Bayís large acreage of mudflats, many biologists consider it to be one of the regionsí most important areas for shorebirds.

TIDAL MARSHES

Tidal marshes are found in the intertidal zone along the Bay edge between mean tide level (MTL) and just above mean higher high water (MHHW). They consist primarily of areas completely open to tidal influence including tidal channels. They also include areas of muted tidal marsh, which are areas where culverts or other obstructions reduce the range of tides but still allow frequent inundation. Salt marshes develop along the shores of protected estuarine bays and river mouths, as well as in more marine-dominated bays and lagoons. Most of California's coastal wetlands are estuarine salt marshes with associated tidal channels and mudflats.

Tidal marshes are at a higher elevation than the tidal zone in tidal mudflats. The tidal marshes are vegetated wetlands that regularly receive some tidal action, though unlike the tidal mudflats they are not completed inundated by the tides. Pacific cordgrass and common pickleweed as well as other specialized plants that can tolerate tidal saltwater, grow in the tidal marshes.

High quality tidal marshes contain intricate networks of channels through which the tides move in and out of the marsh complex. During very high tides shallow depressions called salt pannes hold water within the marsh for weeks. Tidal marshes provide critical habitat for an array of species including young salmon and steelhead trout, shorebirds and ducks that forage in the salt pannes, and mammals like the endangered salt marsh harvest mouse.

MUTED TIDAL/MANAGED PONDS

Both muted tidal ponds and managed ponds are wetlands that are diked. Muted tidal ponds may have limited tidal exchange through culverts or small channels. The water exchange through the culverts and pipelines is limited, so that the change in water level in the ponds is small (usually a few inches) compared to the range of tidal change in other marsh areas (several feet). Managed ponds are shallow open water habitat with no tidal flow. These wetlands contain water all year long and can have various salinities, from low salinity (similar to seawater) to high salinity (3 times or more seawater salinity). The ponds can vary in depth from very shallow (less than 12 inches) to deep (more than 3 feet). Muted tidal marshes exhibit many of the same features as fully tidal marshes, but they often lack the plant diversity due to the limited tidal range.

Muted tidal and managed ponds provide feeding and roosting (resting) areas for waterfowl. Under the right conditions (water depth and salinity) muted tidal ponds provide feeding areas for large populations of waterfowl. The water depth and salinity affect the types of vegetation, insects, and other invertebrates that live in the ponds. The specific types of waterfowl feeding in a pond depend on the specific conditions in the pond; for example, shore birds like shallow ponds, and certain other birds like to feed on brine shrimp, which only live in higher salinity ponds.

SALTWATER EVAPORATION PONDS (SALT PONDS)

Currently, most of the project area is composed of saltwater evaporation ponds. These ponds are a habitat for a variety of microorganisms, insects, and crustaceans that are foodstuff for small fish and waterfowl. The salinity of the ponds varies, and has a major influence on the type of organisms that live in individual ponds. By absorbing and releasing heat energy more slowly than adjacent land areas, the ponds also help to moderate climatic conditions in the area. The extensive levee systems surrounding the ponds provide roosting and nesting areas for a variety of birds, including the least tern (an endangered species), snowy plover (a "species of special concern"), and numerous waterfowl.

SEASONAL WETLANDS

Most seasonal wetlands in the project area are former tidal marshes that have been closed off from the Bay's tidal action by the construction of dikes and levees. With each year's winter rains, these low-lying areas fill with fresh water, and then slowly dry out after the rainy season ends. Salt grass, bulrush, and cattails near the Bay are species typically found in seasonal wetlands. Other depressions in the upland area where saline soils support marsh species may also be seasonal wetlands. Seasonal ponds and marshes create a habitat bonanza for Bay Area wildlife. Ducks, shorebirds, egrets and herons feed and rest here; hawks, owls, coyotes and fox hunt the small mammals of the marshes; black-tailed deer feed on the soft marsh plants.

RIPARIAN CORRIDORS AND FRESHWATER MARSHES

Along streams and rivers flowing into the Bay are riparian corridors and freshwater marsh. Riparian wetlands, which occur on the edge of steams, rivers, and lakes, commonly feature woody vegetation such as red alder, wax myrtle, and willow. Riparian habitats are characterized by lush vegetation and a rich diversity of species. Elderberries, wild rose, and blackberries grow beneath willow, oak, laurel, sycamore and cottonwood trees. Songbirds, woodpeckers, hawks, owls, frogs, snakes, skunks, raccoon, coyote and deer thrive here. Healthy riparian corridors are critical habitat for local spawning salmon, steelhead trout and other anadromous fish.

Freshwater marshes occur in freshwater ponds, low lying areas that accumulate runoff, and slow-moving segments of streams. They are vegetated mostly with herbaceous plants, predominantly cattails, sedges, and rushes. Freshwater marshes have mineral soils that are less fertile than those of salt marshes, and exhibit a greater variety of plant species than do salt marshes.

REFERENCES USED:

Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals, SF Bay Area Wetlands Ecosystem Goals Project

Feasibility Analysis: South Bay Salt Pond Restoration, Siegeland Bachand

Turning Salt into Environmental Gold, Save the Bay

Wetland Overview, EPA fact sheet 843-F-01-002a

Types of Wetlands, EPA fact sheet 843-F-01-002b

Restoring the Estuary: An Implementation Strategy for the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture. January 2001

Shaw, Samuel P. and C. Gordon Fredine 1956. Wetlands of the United States - their extent and their value to waterfowl and other wildlife. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. Circular 39. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Home Page.

Habitat Benefits of Wetlands

WETLAND HABITAT BENEFITS FOR BIRDS

One of the best known functions of wetlands is to provide a habitat for birds. Birds use wetlands for breeding and rearing young. Birds also use wetlands for feeding, resting, shelter, and social interactions. Some waterfowl, such as grebes, have adapted to wetlands to such an extent that their survival depends on the availability of certain types of wetlands within their geographic range. About one-half of the 188 animals that are federally designated as endangered or threatened in the U.S. are wetland-dependent (Niering, 1988). Of these federally listed animals, 17 are bird species or subspecies. http://water.usgs.gov/nwsum/WSP2425/images/table5a.jpeg.

There are both migratory and resident species inhabiting the San Francisco Bay wetlands. Some species like the American avocet and black necked stilt use the tidal marsh for nesting and breeding. Western sandpipers, marbled godwits, and long-billed dowitcher are migratory shorebirds that use the Bay wetlands for resting and feeding. The largest number of individuals of these species have been found in the far North Bay and far South Bay and along the east side of the South Bay. The Ridgway's rail is resident specie that inhabits tidal marsh specifically where cordgrass and pickleweed occur. It nests along channels and feeds throughout the intertidal zone of San Francisco Bay. Other resident species that rely on the tidal marsh include salt marsh yellowthroat, salt marsh song sparrow, and the California black rail. Herons and egrets are along tidal sloughs and shallow ponds although they prefer to nest in tall trees.

For most wetland-dependent birds, the loss of breeding habitat translates directly into smaller populations. As wetlands are destroyed, some birds may move to other less suitable habitats, but reproduction tends to be lower and mortality tends to be higher. The birds that breed in these poorer quality habitats may not contribute to a sustainable population through the years (Pulliam and Danielson, 1991).

Wetlands provide food for birds in the form of plants and invertebrates such as shellfish. Birds also feed on small mammals and other birds. Some birds forage for food in the wetland soils and tidal mudflats, some find food in the water column, and others feed on the vertebrates and invertebrates that live on submersed and emergent plants.

Birds find shelter in wetland vegetation from predators and the weather. The presence or absence of shelter may influence whether birds will inhabit a wetland or a nearby upland area. Predators are likely to abound where birds concentrate, breed, or raise their young. Tidal channels and islands in wetlands are a barrier to land-based predators and reduce the risk of predation to nesting or young birds. However, some predators, such as the raccoon, are well adapted to both wetland and upland environments, and take large numbers of both young and nesting birds. Snakes, fox, feral cats, rats, predatory birds, and other animals take their toll as well. The same vegetation that hides birds from predators also provides some shelter from severe weather. During cold and stormy weather, waterfowl such as canvasback ducks protect their young from windchill in the shelter of a marsh.

Shorebirds are among the most conspicuous wildlife of the North and South bays. Thirty-eight species of wintering and migratory shorebirds were found in the Bay between 1988 and 1995 on surveys performed by the Point Reyes Bird Observatory (PRBO). Total numbers of shorebirds on these surveys ranged from 340,000ñ396,000 in the fall, 281,000ñ343,000 in the winter, to 589,000ñ838,000 in the spring. Approximately two-thirds of the migrating and wintering shorebirds occurred in the South Bay. These birds prefer to feed in the mudflats but will use open marsh areas, levees and islands during high tide when the mudflats are covered.

The San Francisco Bay area is one of the most important coastal wintering and migratory habitats for Pacific Flyway waterfowl populations. They do not breed in the Bay but use it during migration for feeding and resting. The San Francisco Bay is particularly important to the future of canvasback and other diving duck populations of the Pacific Flyway. Significant numbers of the Pacific Flyway scaup (70%), scoter (60%), canvasback (42%), and bufflehead (38%) were located in the San Francisco Bay/Delta. According to the 1998 California Fish and Wildlife surveys, San Francisco Bay held the majority of Californiaís 1999 wintering scaup (85%), scoter (89%), and canvasback (70%) populations. More than 56 percent of the Stateís 1999 wintering diving ducks were located in the San Francisco Bay proper, which includes the salt ponds and wetlands adjacent to the North and South Bays. Although the San Francisco Bay is most recognized for its importance to diving ducks, large numbers of dabbling ducks like pintail (23,500 birds) and widgeon (14,000 birds) were observed during the 1999 midwinter waterfowl survey.

WETLAND HABITAT BENEFITS FOR FISH

Wetlands and deep waters of the San Francisco Bay provide important habitat for a wide variety of fish and shellfish. Subtidal eelgrass beds shelter larval and juvenile fish, as well as many species of invertebrates. Salt marshes and shallow water areas provide habitat for larval, juvenile, and adult fishes and shellfish including shiner perch, topsmelt, staghorn sculpin, striped bass, and bay shrimp. Common fishes of the Central and South Bay tidal marshes include arrow goby, yellowfin goby, and staghorn sculpin. Important commercial and sport fishes that utilize deepwater habitats include northern anchovy, starry flounder, striped bass, king salmon, sturgeon, steelhead, and American shad. The Coho salmon and the steelhead, two federally threatened fish, species occur in the vicinity of the South Bay.

WETLAND HABITAT BENEFITS FOR MAMMALS

Few mammals are as closely tied to wetlands as are many birds, but many mammals exploit abundant food supplies or shelter during certain periods of the year. The most abundant marine mammal associated with wetlands and deepwater habitats of the Bay is the harbor seal. This species uses tidal salt marshes and mudflats for breeding, hauling out (resting out of the water), and raising their young and deepwater habitats for foraging. The sea lion is another important marine mammal of the San Francisco Bay.

Tidal marshes also provide habitat for small mammals including the Suisun shrew, salt marsh wandering shrew, and salt marsh harvest mouse. The endangered salt marsh harvest mouse and the Suisun shrew are totally dependent on wetlands. The salt marsh harvest mouse can be found in salt and brackish habitat and in diked and tidal areas. They hide in dense pickleweed, which they use for food and shelter.

WETLAND HABITAT BENEFITS FOR PLANTS

Wetlands are home to a community of plants including green algae, red algae, sea lettuce, eelgrass, pickleweed, and cordgrass. Wetland plants are specialized in that they have adapted to the variations in salinity and soil saturation or partial submergence. However, more than 50 plant species found in the Bay marshes at the turn of this century are now extinct or exist in isolated populations. Locally extinct species include sea-pink, salt marsh owl's clover, and smooth goldfield (all eradicated throughout the South Bay); and California sea-blite and California saltbush (eradicated throughout the Estuary). Today, tidal marshes are home to rare plant species such as the Point Reyes birdís-beak, soft birdís beak, Suisun thistle, Masonís lilaeopsis, and Delta tule pea.

Wetland plant communities vary markedly from one part of the San Francisco Estuary to another. The variation correlates strongly to salinity patterns and to other factors such as substrate, wave energy, marsh age, sedimentation, and erosion. For example, a tidal marsh on Montezuma Slough in Suisun, which has tall tules and cattails along the channels, looks very different compared to a tidal marsh on the Palo Alto bay front which has low-growing pickleweed and Pacific cordgrass along the channels. Additional plant species on tidal marsh include fat hen, marsh rosemary, alkali heath, and jaumea. Levees within tidal marshes support coyote brush and gum plants.

REFERENCES USED:

Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals, SF Bay Area Wetlands Ecosystem Goals Project

Feasibility Analysis: South Bay Salt Pond Restoration, Siegel and Bachand

Turning Salt into Environmental Gold, Save the Bay

Wetland Overview, EPA fact sheet 843-F-01-002a

Restoring the Estuary: An Implementation Strategy for the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture. January 2001

Shaw, Samuel P. and C. Gordon Fredine. 1956. Wetlands of the United States - their extent and their value to waterfowl and other wildlife. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. Circular 39. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Home Page.

he Ecology of San Francisco Bay Tidal Marshes: A Community Profile, FWS/OBS-83/23

Faber, Phyllis M. 1982. Common Wetland Plants of Coastal California: A Field Guide for the Layman. Pickleweed Press

http://ceres.ca.gov/ceres/calweb/coastal/wetlands.html

http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/1998/uswetlan/uswetlan.htm (Version 05JAN99).

http://endangered.fws.gov/wildlife.html

http://www.watres.com/topics/tp-wetlands.html

http://water.usgs.gov/nwsum/WSP2425/images/table5a.jpeg

Threatened and Endangered Species

WHAT ARE THREATENED AND ENDANGERED SPECIES?

An "endangered" species is one that is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range. A "threatened" species is one that is likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future. The US Fish and Wildlife Service also maintains a list of species that are candidates or proposed for listing as threatened or endangered. In California, the state has designated two additional categories: rare species, and species of special concern. Collectively, endangered, threatened, rare, special concern species are referred to as special status species. Special status species may be animals (including birds, fish, and insects), or plants.

Today there are 50 species of plants and animals (26 animal and 22 plant species) that occur in or near San Francisco Bay wetlands that are listed as threatened of endangered under the state and federal endangered species act. In addition to state and federally listed species, the Bay Area is home to 16 fish and wildlife species and 13 plant species associated with wetlands that are candidate or proposed candidate species for federal endangered or threatened status.

Definitions (both federal and State of California definitions) are provided in the glossary.

CALIFORNIA’S SPECIAL STATUS SPECIES

There are 296 threatened and endangered species in California -- 116 animals and 180 plants. Marsh birds like the snowy egret, great egret, black crowned night heron, great blue heron and California clapper rail take advantage of nesting habitat in the San Francisco Estuary. The different types of wetlands provide habitat for different types of endangered species. Below is a list of different wetland habitats and the special status species typically found at these habitats.

| Tidal Mudflat | Tidal Marsh | Seasonal Wetland | Riparian |

| Snowy plover Pacific herring Marbled godwit Western sandpiper Starry flounder California least tern | Chinook salmon Dungeness crab Ridgway's rail Salt marsh harvest mouse Black rail Ribbed horsemussel | Northern pintail Long-billed dowitcher Western pond turtle Savannah sparrow California vole Ruddy duck Pygmy blue butterfly | Red legged frog Yellow warbler California toad River otter Pacific treefrog Alligator lizard Black-crowned night heron |

For a list of threatened and endangered species for the San Francisco Bay Estuary, please refer to the Baylands Habitat Goals Report (http://www.sfei.org/sfbaygoals/) or the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture Restoring the Estuary Report(http://www.sfbayjv.org/estuarybook.html).

References Used:

Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals, SF Bay Area Wetlands Ecosystem Goals Project

Turning Salt into Environmental Gold, Save the Bay

Restoring the Estuary: An Implementation Strategy for the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture. January 2001

Shaw, Samuel P. and C. Gordon Fredine 1956. Wetlands of the United States - their extent and their value to waterfowl and other wildlife. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. Circular 39. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Home Page.

http://ceres.ca.gov/ceres/calweb/coastal/wetlands.html

http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/1998/uswetlan/uswetlan.htm (Version 05JAN99).

http://endangered.fws.gov/wildlife.html

http://www.watres.com/topics/tp-wetlands.html

http://water.usgs.gov/nwsum/WSP2425/images/table5a.jpeg

http://www.audubonsfbay.org/sfbay_2_16/learn_wild.html

http://www.audubonsfbay.org/sfbay_2_16/learn_wild.html

Flood Control Benefits of Wetlands

Many factors contribute to flood conditions and affect the severity of damage including: precipitation, slope, land use, soil type, water table level, amount of impervious surface, climate, and dams. Wetlands are considered ìnatural spongesî and have tremendous capacity to act as natural flood control. When rivers overflow during rain events, wetlands help absorb and slow floodwaters. This ability to control floods can significantly prevent property damage and loss and can save lives. Each wetland has itís own hydrology and holds water differently. Some wetlands are ìflow-throughî wetlands. However, when water flows through a wetland, it is slower than when it rushes down a stream. Studies have found that when wetlands are destroyed, flooding increases significantly.

In contrast to narrower streambeds and channels, the wider open areas in wetlands and their vegetation can slow the speed of floodwaters. The floodwaters then continue more slowly into a river or stream, evaporate into the atmosphere, and recharge the groundwater. Wetlands also function to trap sediment and debris as the speed of the water slows and the debris settles out. By reducing the rate and amount of storm water entering the river or stream, wetlands lessen the destructiveness of the flood.

Wetlands within and downstream of urban areas are particularly valuable, counteracting the greatly increased rate and volume of surface water runoff from pavement, buildings and other impervious surfaces. The holding capacity of wetlands helps control floods and can act as a natural storm water retention pond. Preserving and restoring wetlands, together with other water retention, can often provide the level of flood control otherwise provided by expensive dredge operations and levees.

References Used:

Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals, SF Bay Area Wetlands Ecosystem Goals Project

Feasibility Analysis: South Bay Salt Pond Restoration, Siegeland Bachand

Turning Salt into Environmental Gold, Save the Bay

Wetland Restoration, EPA fact sheet 843-F-01-002e

Wetland Overview, EPA fact sheet 843-F-01-002a

Restoring the Estuary: An Implementation Strategy for the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture. January 2001

http://ceres.ca.gov/ceres/calweb/coastal/wetlands.html

http://www.watres.com/topics/tp-wetlands.html

Wetland Restoration

What is Wetland Restoration?

Restoration is the return of a degraded wetland or former wetland to its preexisting, naturally functioning condition, or a condition as close to that as possible. Restoration projects require planning, implementation, monitoring and management, using a team with expertise in ecology, hydrology, engineering and environmental planning.

Why Restore Wetlands?

Restoring lost and degraded wetlands is essential to ensure the health of our watersheds. Over the past 200 years, wetlands have vanished at an alarming rate; in the Bay Area, it is estimated that 95% of the Bay’s historic tidal wetlands have been destroyed. Such losses hamper wetland functions, such as water quality protection, habitat for fish and other wildlife, and flood protection.

Restoration Goals of the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project

The goal of South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project is to improve the physical, biological, and chemical health of the San Francisco Estuary by restoring over 15,000 acres of Cargill salt ponds to wetlands. The restoration planning effort will integrate restoration with flood management, while also providing for public access, recreation, and education opportunities. Ultimately, the area will be a combination of tidal marsh and managed ponds, with channels and corridors of similar habitat connecting these areas.

Wetlands Restoration in the San Francisco Bay Area

Wetlands restoration is a relatively “young” science. Wetland restoration efforts have been underway in the Bay Area since the late 1960’s, and much has been learned from the successes and failures of these projects. Selecting suitable sites and relying on natural processes emerge as key factors for successful restoration.

Considerations for the South Bay Restoration Project

Salt production in the San Francisco Bay Estuary has been going on since the 1860’s. The current network of South Bay salt production ponds have been in operation for the last 50 years. These salt ponds have altered the South Bay ecosystem in two ways. These shallow ponds have changed the Bay’s natural hydrology and degraded water quality; at the same time, these salt ponds have been providing valuable waterfowl habitat. While salt pond restoration will benefit some species, other species may be negatively impacted by the loss of salt pond habitat. Restoration must balance these habitat needs.

Physical Conditions and Hydrology

There are several physical conditions that will affect the feasibility of restoring salt ponds to tidal marshes: presence of channels, availability of material for levees, pond subsidence, potential for flooding, and infrastructure impediments (railroad crossings, bridges, underground pipes, etc.). Groundwater pumping has caused significant subsidence in some of the ponds, making revegetation difficult. Also, in order to restore natural tidal flow to marshes, the proximity to tidal waters, the existence of channels and other factors must be considered. It will also be important to integrate the need for flood control levees with the levees required for wetland restoration.

Invasive Species

Restoration may provide new habitat for invasive non-native species. Invasive species are non-native species that displace native species by either out-competing them for available habitat, by predation, or by introducing diseases. Invasive species are extremely harmful to native species. In the South Bay, smooth cordgrass, Norway rat and red fox are the non-native species of concern. Newly restored wetlands are particularly vulnerable to invasion by smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), and no satisfactory control measure has yet been identified. The non-native Norway rat and red fox prey on the eggs of nesting birds, so restoration must find ways to limit access to nesting areas.

Managed Ponds

Not all of the 15,000 acres will be restored to tidal marshes. Factors that will be considered are the wildlife habitat needs and the existing conditions of the salt ponds. In some pond areas there are conditions that exist which make tidal marsh restoration extremely difficult ñ need for flood control levees, severe pond subsidence, infrastructure that interferes with tidal movement, residual high salinity. These areas may be used for other types of habitat, such as managed ponds (shallow open water habitats) and salt pannes (flat, unvegetated hypersaline areas with seasonal ponds). Water depths in managed ponds can range in depth from a few inches (preferred by shore birds) to deeper than 3 feet (required for diving ducks). Salinities in managed ponds may also vary.

Adaptive Management

Restoration of wetlands is a dynamic process, and natural conditions and the wildlife use of the ponds vary from year to year. The timing of the restoration activities will be important not only to avoid disturbing wildlife species but also to ensure that earlier phases of the restoration have been successful before altering other habitat. It will be necessary to carefully monitor conditions as the restoration proceeds, and adapt the restoration plans to ensure overall project goals are achieved.

References Used:

Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals, SF Bay Area Wetlands Ecosystem Goals Project

Feasibility Analysis: South Bay Salt Pond Restoration, Siegeland Bachand

Turning Salt into Environmental Gold, Save the Bay

Wetland Restoration, EPA fact sheet 843-F-01-002e